Against the Best Possible Sources

2019

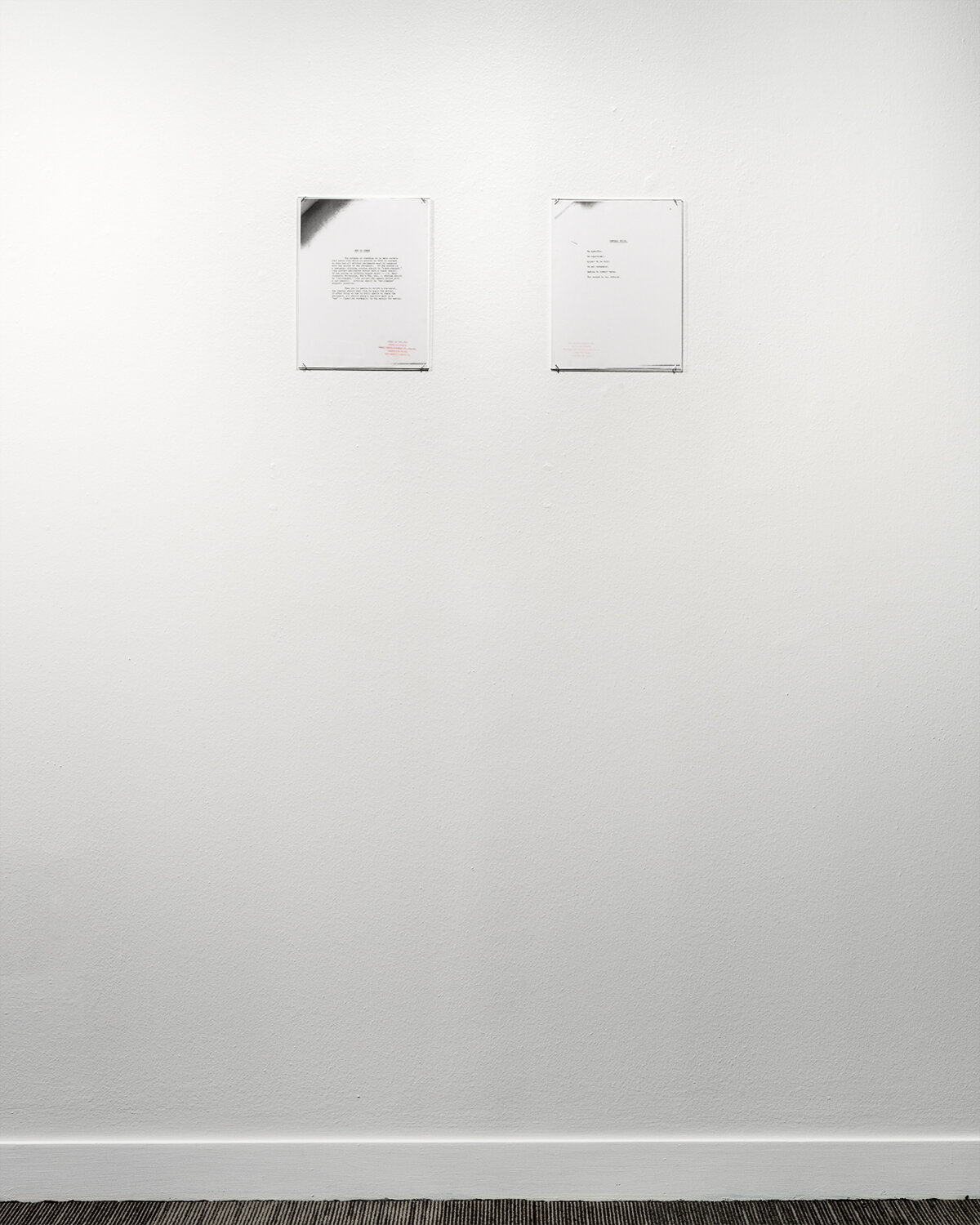

installation view - Multi-media installation, stereo digital audio recording, runtime 10min

Against the Best Possible Sources

by Elizabeth Moran

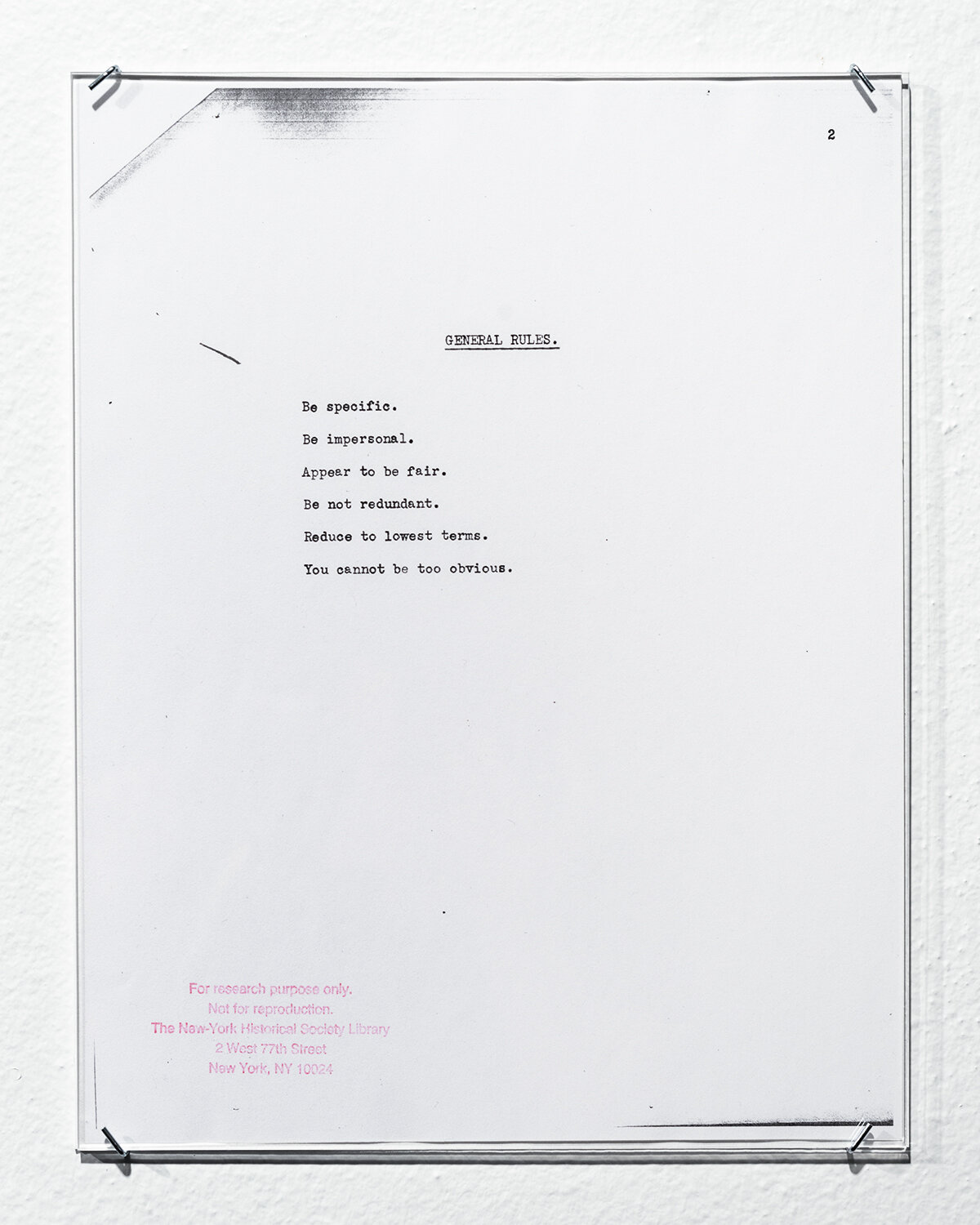

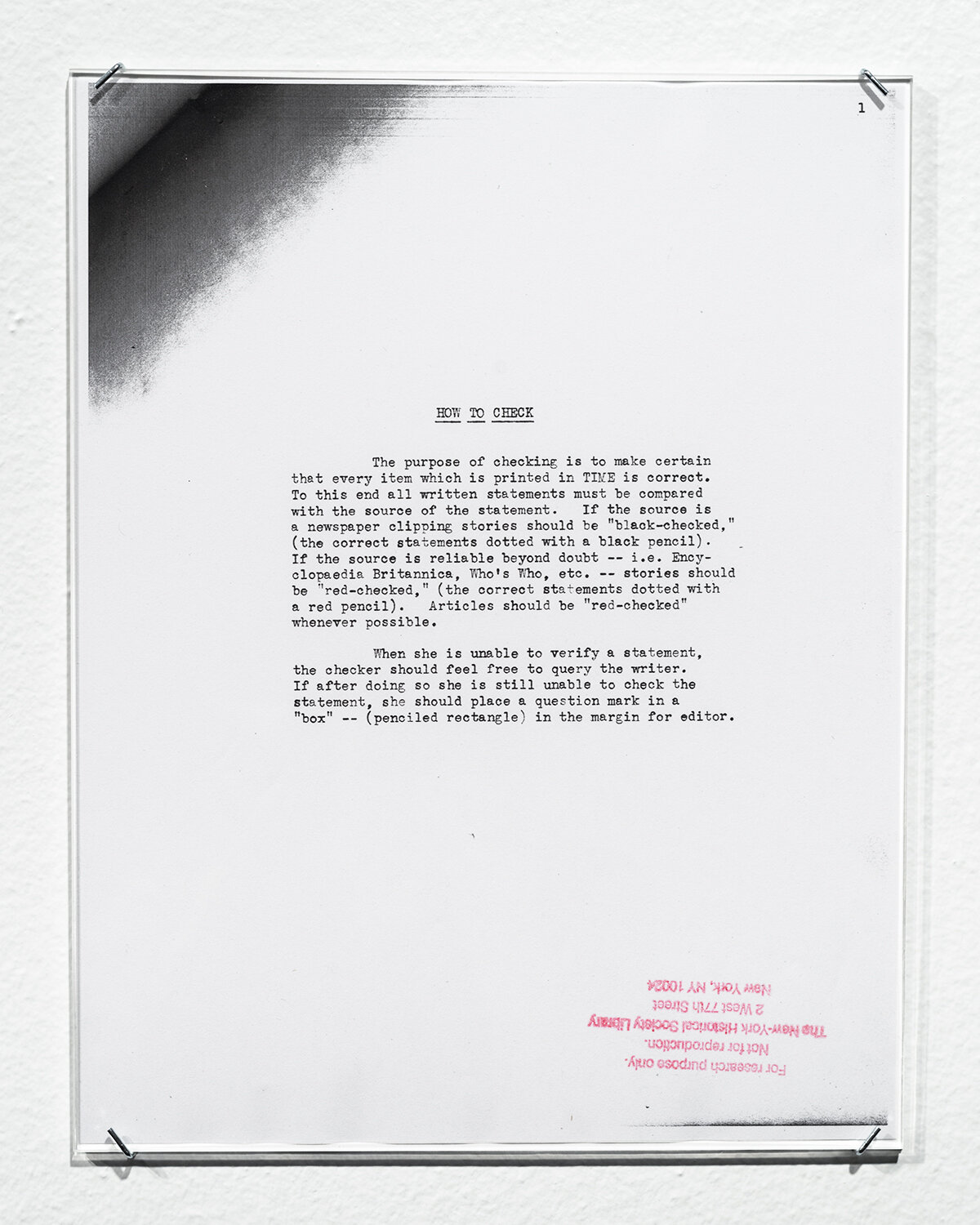

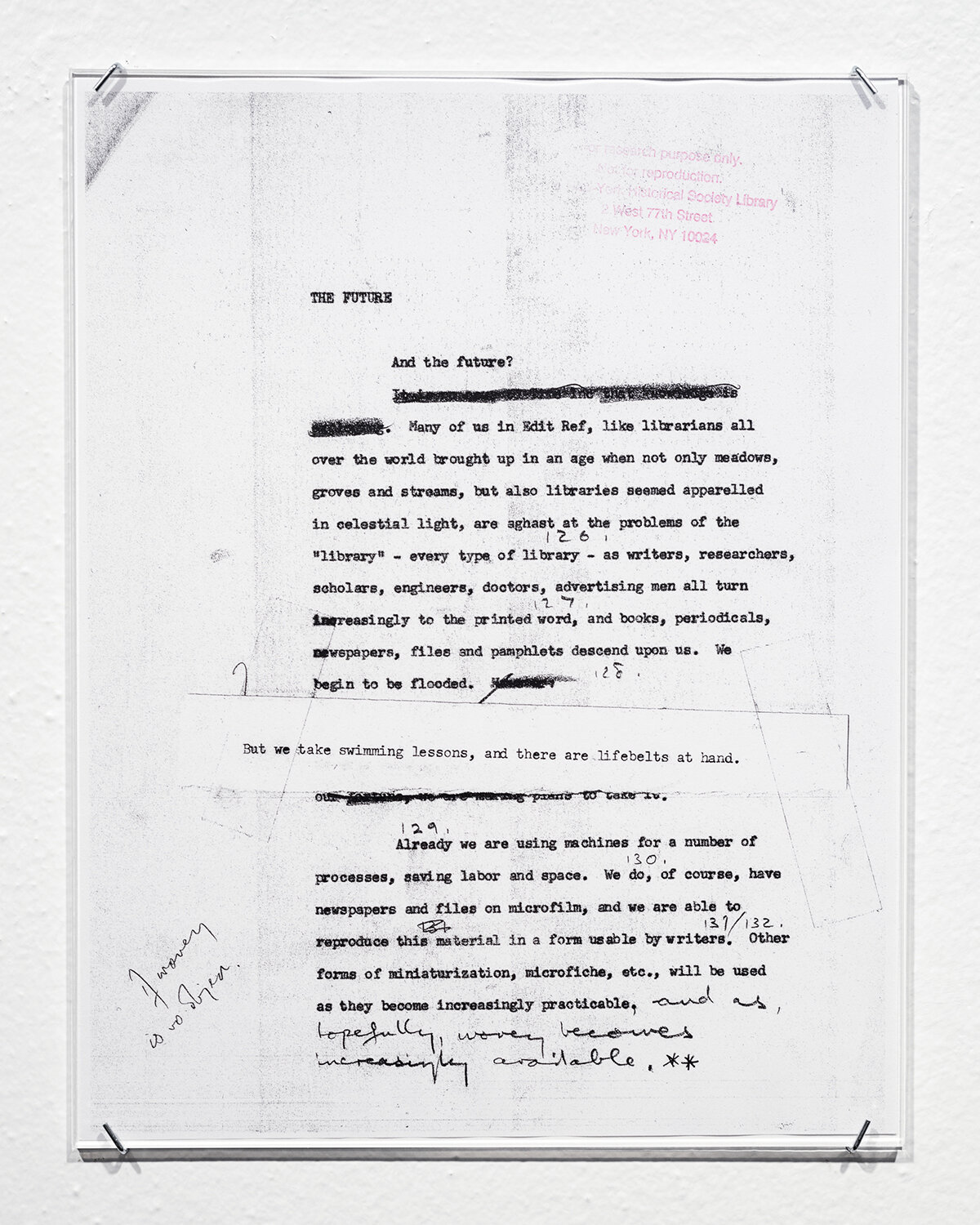

Against the Best Possible Sources (on view September–December 2019 at Southern Methodist University’s Hawn Gallery in Dallas, Texas) presents the latest chapter of my ongoing project involving extensive research of the TIME, Inc. corporate archive and an investigation of the earliest history of the first professional journalistic fact-checkers, a role created by TIME in 1923 and held exclusively by women until 1971. Few first-person accounts of the women’s experiences remain. Instead, the majority of their stories are found only through internal correspondences with their male colleagues still preserved in the company’s archives: hand-drawn cartoons, scribbled notes, and reminiscences capture the prevailing sexism of the time—a sustained male gaze through which the women and their work was seen, recorded, and mythologized.

In this installation, I recompose these questionable, secondary sources creating a new narrative that is both unreliable but also the most comprehensive account of the first fact-checkers that exists today. Against the Best Possible Sources consists of decommissioned library shelves sourced from SMU’s Hamon Arts Library, decommissioned library books, dye-sublimation printed steel bookends, stamped photocopies created by TIME, Inc. archive librarians, and a decommissioned Kodak Carousel 860H slide projector with eighty 35mm slides. The accompanying audio piece utilizes creative nonfiction strategies including a newly commissioned musical duet to unveil the simultaneous presence and absence of these women and their contribution to modern journalism.

Reacting against the sensationalized, tabloid journalism of the Progressive Era, TIME originally advertised their reporting as “written after the most exhaustive scrutiny of news-sources” with confirmed, reliable facts as its primary innovation and product. Indeed founders Henry Luce and Briton Hadden originally considered naming the weekly news magazine Facts. However this “exhaustive scrutiny” was considered women’s work from its inception: employment requirements found in early fact-checking manuals specified that checkers must be under age thirty, must be blonde, must wear stockings and specific gloves depending on the time of year, must wear hatpins under 6-inches in length and that checkers must maintain their “domestic list of chores.”

While female fact-checkers were considered subordinate to the male staff writers, the checkers had the power to kill any story that they could not verify—a decision that would impact a writer’s income. One such writer, Roger S. Hewlett, rewrote the lyrics to American composer Irving Berlin’s major Broadway hit, “You’re Just In Love,” and sarcastically serenaded the checkers whenever they would kill one of his stories. For this installation, I commissioned young Broadway singers to perform Hewlett’s rendition, “Checking Time (A duet in descant),” which flagrantly includes the refrain, “They’re not lies, they’re just not true.”

The first fact-checker was hired in early 1923 and proceeded to lay the groundwork for fact- checking processes still in use to this day by supplying and verifying the facts for TIME, Inc.’s writers. However the only three reference books available to the early checkers were The Bible, Homer’s Iliad, and Xenophon’s Anabasis. For any other references or research, they went to the New York Public Library, which they used as a second office. By 1929 the female employees began organizing their years of research for TIME into their own in-house library, nicknamed the Morgue. By the 1960s, the Morgue had grown to include 83,000 books and 500,000 folders of reference material and continued expanding through the 1990s when it was renamed the Time Warner Research Center. Over time, the primary sources used by the fact-checkers have been retired into storage or eliminated completely. Following a merger in 2001, AOL Time Warner announced the closing of the Research Center and laid-off its thirty- six full-time researchers. The archive is now housed within the New York Historical Society in Manhattan.

In this exhibition, I conflate this loss of primary sources with the untold stories and contributions of the early fact-checkers through photography, text, sound, and other forms of recorded documentation. The ten-minute audio narration by the artist is constructed from found texts sourced exclusively from the TIME, Inc. archive and published in this booklet as a visual collage. Presented in the installation as stereo sound, I position male narration and supposedly objective information through the left speaker, while women’s subjective statements in the first person can be heard through the right speaker. The result is a ping-ponging chorus of anonymous voices all told and equalized through the artist’s own. Decommissioned library shelves found at SMU’s Hamon Arts Library are presented as skeletal remains emptied of their contents. Scattered throughout the shelves are artist-made bookends rendered useless save for their surfaces, which display images of found artifacts and office materials entombed in TIME, Inc.’s archive. Only decommissioned library books of The Bible, Homer’s Iliad, and Xenophon’s Anabasis linger, replicating TIME Inc.’s first library now deemed unwanted—bearing the stamps of the libraries from which they were discarded.

The three books which formed TIME’s original library—the Bible, Xenophon’s Anabasis, and the Iliad

Decommissioned library books, The Holy Bible,

Xenophon’s Anabasis, Homer’s Iliad (unique)

Dimensions variable - (Installation detail)

The Kodak Carousel slide projector flickers in the back of the gallery briefly illuminating photographs, internal memos, records, and other ephemera which shed light on the original fact-checkers. The slide projector itself, first patented in 1965 and discontinued in 2004, presents a media technology that was both invented and subsequently discarded within the time period of my research. The projected images were made with my cell phone during my visits to the archive and were backwards-translated into slide film for this exhibition. This photo montage displays the employees and environment of TIME, Inc. and are not presented in chronological order. My own hand can be seen arranging and proffering these documents—the limb of yet another disembodied researcher comingling with the unidentified individuals in the pictures. Visually presented in an analog format which exudes a credible formality, but the eighty 35mm film slides—blasted by the light and heat of the mechanical operations—degraded over the course of the exhibition.

Against the Best Possible Sources

2019

Multi-media installation, stereo digital audio recording, runtime 10min

(Installation detail)

Through my inquiry, I embody the processes of these women by reperforming their meticulous labor and present my own subjectivity—my selection of texts, images, and choices in framing and cropping of photographs—becomes the buried content the viewer unearths. The installation moves in and out of various time periods like shadow play, sound and image bleeding together into an almost ungraspable abstraction. As one TIME, Inc. memo from 1967 states, “Without highly sophisticated methods of addressing stored data, we are lost.” Amid decommissioned objects and archaic technology, I position my research as verifiable, interrogating the historical association between women’s work and fact-checking, while simultaneously examining the reliability of the information itself.

Against the Best Possible Sources

2019

Multi-media installation, stereo digital audio recording, runtime 10min

Dimensions variable

Southern Methodist University’s Hawn Gallery

Dallas, Texas

Exhibition on view September 15 – December 15, 2019

Curated by Olivia Smith

all images courtesy Elizabeth Moran

Elizabeth Moran (b. 1984, Houston, Texas) lives and works in New York. She received her Master of Fine Arts and Master of Arts in Visual and Critical Studies from California College of the Arts in 2014. Moran’s work has been exhibited internationally, most recently at Massimo Ligreggi Gallery in Catania, Italy (2020) and Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas (2019). Her work was recently featured in VICE and The Dallas Morning News.