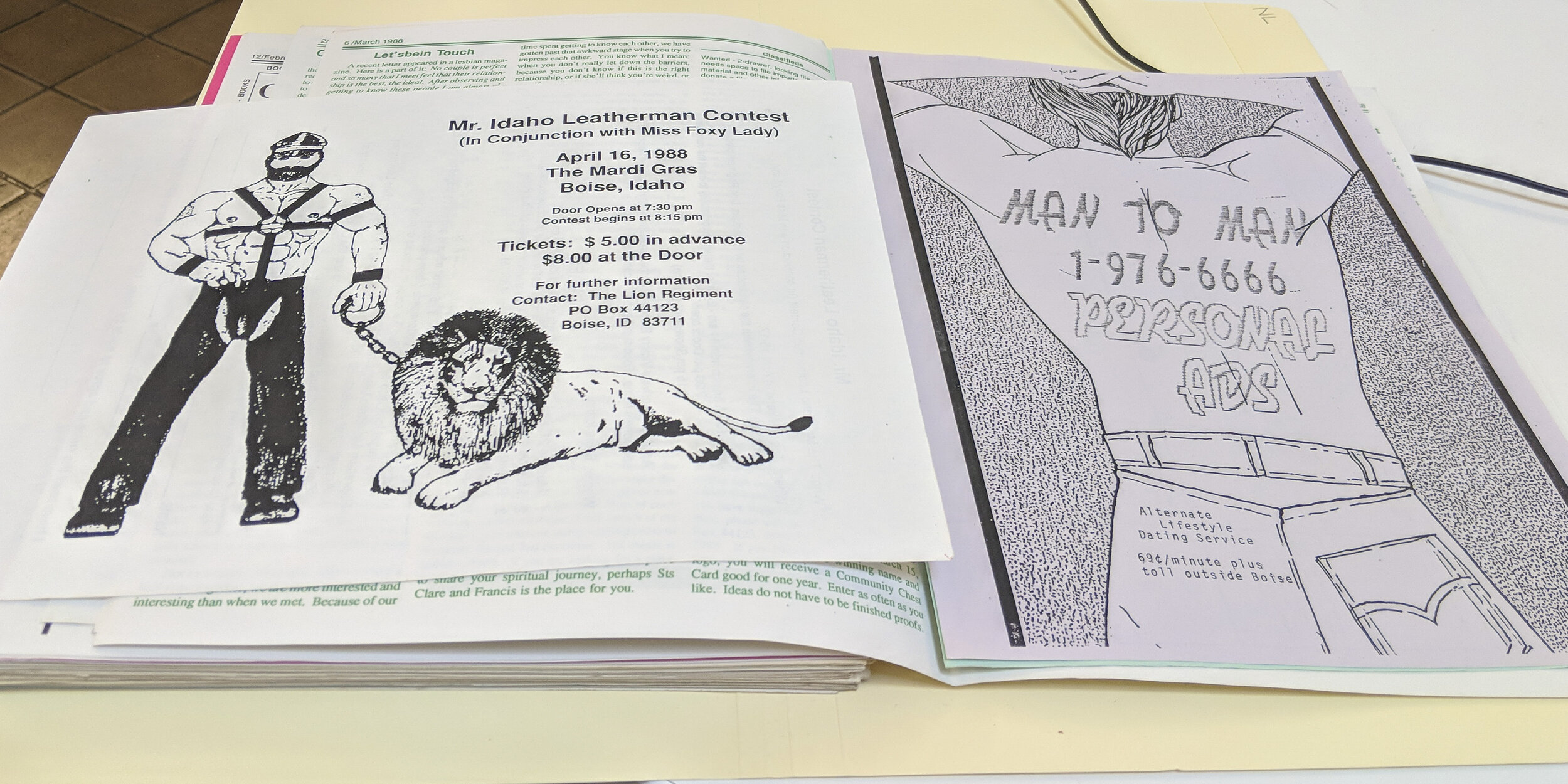

Idaho Mr. Leatherman Assoc. Mardi Gras. April 12, 1988. Handbill. USC. The One Foundation. 1988.

Man to Man Personals. 1988(?). Handbill. USC. The One Foundation. 1988.

How the West was Lost: On Archiving Sex in the Mountain West

by Steacy Easton

A sex scandal happened in Boise in 1955. The sex was between upper class, older, men, and working class younger men. The sex occured in the back rooms of businesses, and in parks, in cars, and in other semi private or public places. Sometimes money was exchanged for sex. The sex resulted in arrests, some hefty fines, some prison time, some people exiling themselves to the coasts, and at least one suicide.

John Gerassi wrote a book on the case, Boys from Boise in the mid 1960s (reissued in 2000), and there was a documentary film fourteen years ago (2006’s The Fall of ‘55)—but it appears that sex between men in Boise ended in 1955. The sexual culture of a place determines the public culture of a place, and a scandal like the one in Boise has decades worth of consequences and at least two levels of archival distance—there is less material about working class people, in general, and specifically historical material about how those people have sex is even rarer.

Working around a set of texts to find a throughline is an act of archival curation which makes it harder for working class queerness to determine itself. It’s easier to self fashion when rent is already paid.

During my visit to One Archives in LA last summer, I found a wide range of materials across lines of class, sexuality, gender expression, and race, however there are still gaps in representation: there is less working class material and the collection still favours big coastal cities.

The Community Foundation. Sweetheart Dance. February 16, 198(?). Handbill. USC. The One Foundation Archives. 198(?)

The Community Foundation. SweetHeart Dance. February 15, 1986. Handbill. USC. The One Foundation Archives. 1986.

The Community Foundation. AIDS Research for Hospice. August, 1985. Handbill. USC. The One Foundation Archives. 1985.

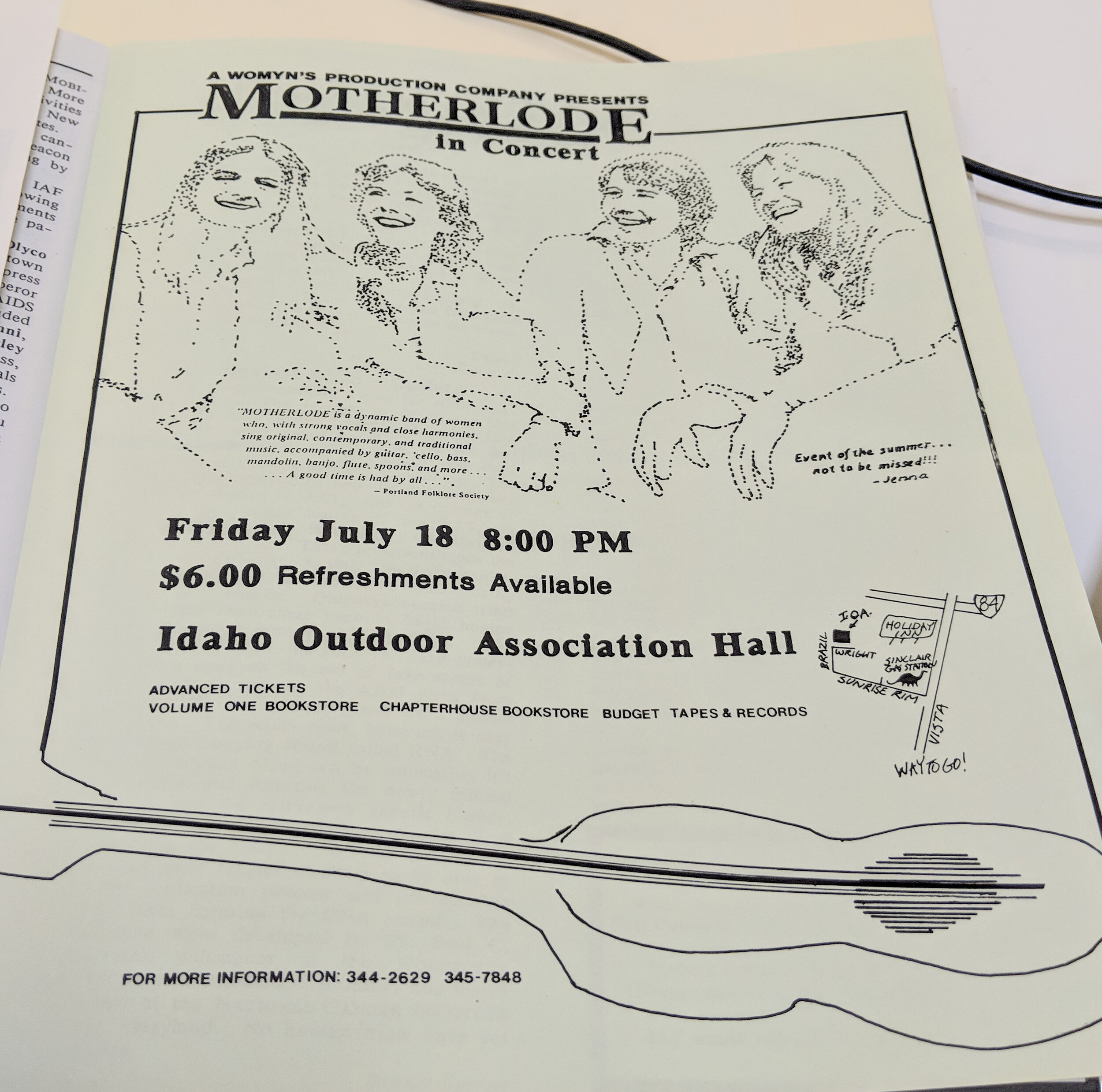

The Community Foundation. Motherlode. July 18, 1986. Handbill. USC. The One Foundation Archive. 1986.

One Archives does have a collection of handbills and newsletters from Boise gay lib from the 1980s to the early 1990s. Most of these were from a newsletter called The Paper for Our Community, the newsletter for a GLBTQ+ organization out of Boise, called the Community Center. Within those finds were various handbills and event notices. None of these publications directly mentioned the boys from Boise, but looking carefully one could find an historical throughline.

1) There were only about 13 newsletters, and maybe a dozen handbills. Most of these copies were mailed to NYC or San Francisco. These organizations ran on a shoestring budget—there might or might not have been more copies or they might not have been mailed or maintained.

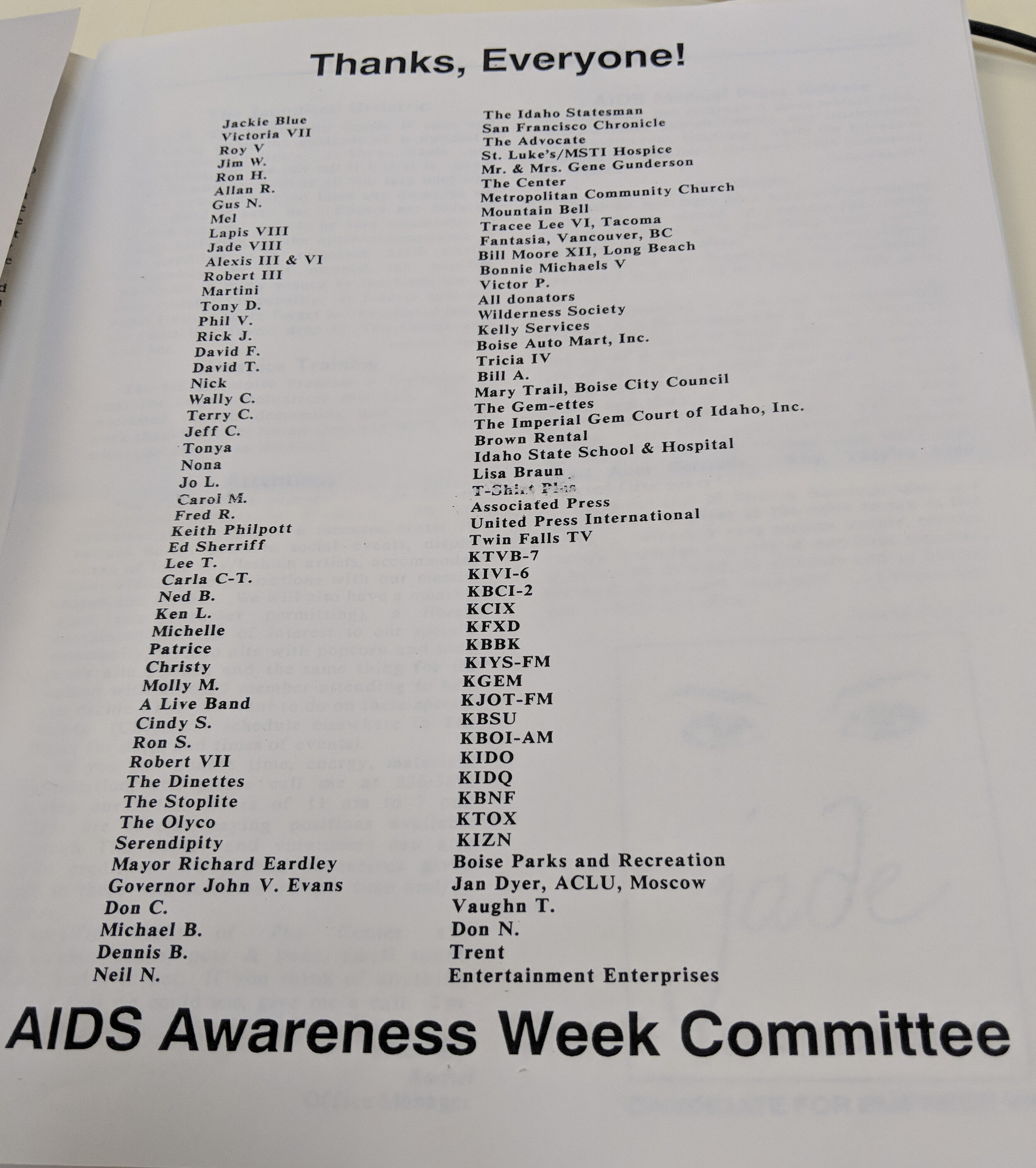

2) The copies had fundraising notices for community centers, newsletter, and later for AIDS charities. The records of these fundraising organizations were not part of the archival collection. There were not minutes from these organizing meetings; nor were there letters from the committees to the mayor’s office or any notes about how they got the radio and television stations involved.

3) Reading through announcements and personal advertisements suggests a whole range of radical potential that is hinted at but not explicitly stated (networks of mutual aid that failed in the 1950s rose again in the 1980s). There was mention of radical lesbian networks in Moscow, Idaho. Where are the records of those Moscow, Idaho lesbians? Where are their archives and where are their stories?

4) In the early 1980s, the “mutual aid” networks realized that AIDS had come to the Mountain West. The first case of AIDS was reported in the Boise suburb of Nampa in late 1984. Many of the arrests and some of the conversations in Gerassi’s book occurred in Nampa. Men had sex with men in Nampa in 1955 and in 1984. What kind of men were embodying which kinds of desire between those two dates?

5) In the fall-out of those early diagnosis of AIDS, a week of fundraising and awareness raising happened in Boise, including support from local TV and radio. The mayor sent a note. It was respectable. Not having immediate access to the archives in non-queer local scenes, the only conversation we have about respectability is one within local communities.

6) There was a gossip column queen named Martini--- Drag name, not the name her mother gave her (another gap in the record). The column is super knowing and incredibly insider and thus self-selecting. In it she wrote in the mid 1980s about cops arresting people for cruising. Some newsletter copies were found in one bar that was always at risk of shutting down. Other copies were mailed out to subscribers. There was a gap between how Martini reported and how the rest of the town selected.

7) The network of those who knew where the bathrooms were, and those who thought bathroom sex was an impediment to queer acceptance must have had some overlap.

8) In 1982, one of the people who was written about in Boys from Boise killed himself. He was the son of a city council member. His name was public and famous in Boise, but became well known to the outside world in 2000, where Gerassi named him in the introduction of a new edition under a pseudonym. Martini was known within the Boise community, her writing winked at the mess of false names, gossip, fact telling, and scandal that measured her hometown. These are their own archives.

The Imperial Gem Court of Idaho. A Night In Gay Paree. Oct. 25, 1985. Handbill. USC. The One Foundation Archives. 1985.

The Imperial Gem Court of Idaho. Art Deco: The Crowning Event. July, 26. 1986. Handbill . USC. The One Foundation Archive. 1986.

The Community Foundation. AIDS Awareness Week Sponsor List. 1984. np. Newsletter. USC. The One Foundation Archives. 1984.

Contrary to the post-digital instinct that everything has been archived, I am more interested in the gaps between public and private; between names intended for interior communities and others for exterior communities; between the ersatz archives of hook-up spots and cruising grounds that aren’t written down (or Grindr profiles) and those published in queer magazines; or between the intricacies of working class communities that seek a kind of placidity and a politically radical edge that finds liberation in public discourse. Working through an archive is to look through each of these contexts—to respect the tenacity of these multitudes of forms.

There is a temptation to write the gaps in this history. I think that this attempt to reach conclusions from limited information is difficult. However, doing the labor of noting the gaps of working class and queer archives, noting what is absent and the desires to complete those gaps—to state and mark the lacunae of representation has its own kind of labor and one that has more integrity than falling for the temptations of a complete record. Noting where the archive is absent is its own kind of history, these absences, their own kind of throughline.

A note on images: documents pictured have not been officially digitized by the One Foundation, and come interleaved from the “The Paper for Our Community”, from The Community Center, an LGBTQ+ organization in Boise Idaho. They are stored at the One Foundation, at USC in Los Angeles. They were accessed in August, 2019. The photos are my own.

(bio image by Brandon Canning)

Steacy Easton is a writer and artist who grew up in Edmonton, and is now living in Hamilton. They write often about the intersections of working class culture and sex.

Substack: https://pinkmoose.substack.com/

Twitter: PinkMoose

IG: PinkMoose4Eva

Works Cited

The community center : resources for gay and lesbian people -- Boise: Community Center, Aug. 1984-Oct. 1984. One Foundation Archives. University of Southern California, Los Angeles. (broken link)

Gerassi, John, and Peter Boag. The Boys of Boise: Furor, Vice & Folly in an American City. University of Washington, 1967, 2001.

Randel , Seth. The Fall of 55 . Frameline, 2006.