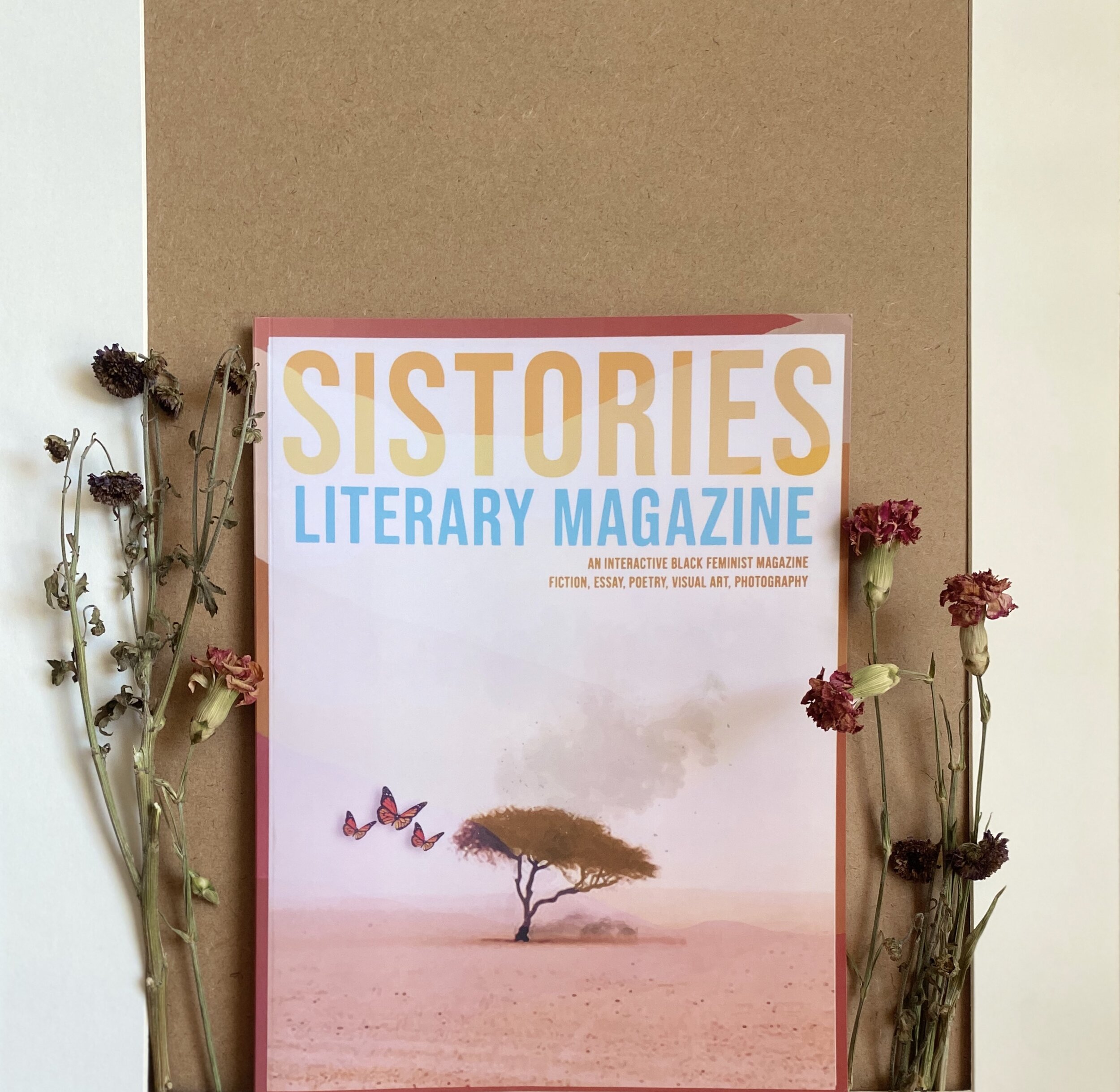

SISTORIES, an Interactive Black Feminist Magazine

SISTORIES

By Ashley Nickens

The Forged Woman, the first issue of SISTORIES was published in early spring. This essay reflects on the literary magazine itself, deeply rooted in Black Feminism, and also on its evolving context within the current moment.

Michelle Russell begins her essay, “Black-Eyed Blues Connections: Teaching Black Women,” by making the claim that “political education for Black women in America begins with the memory of four hundred years of enslavement, diaspora, forced labor, beatings, bombings, lynchings, and rape.” After explaining the awe-inspiring tone political education takes on when we tell stories of the behemoths who tackled these oppressive forces head-on, and the practical tone echoed by our everyday communal confrontations, she goes on to express how political education “becomes radical when teachers “develop a methodology that places daily life at the center of history and enables Black women to struggle for survival with the knowledge that they are making history” (196).

As an educator who was radicalized by Black feminist and womanist literature, I have always been clear that that was my goal for SISTORIES--to provide the grounds for Black women and nonbinary femmes to adopt a politic to address the root cause of the social issues that cause them harm by seeing and writing themselves into the historical narrative of Black femmehood. Yet, despite the clarity with which I have understood the purpose of my work, I still struggle at times to answer the increasingly frequently posed question--why did you start this organization?

When I consider the SISTORIES origin story, there are moments when I trace it to my experience as a Black literature student at a PWI and the failures of this environment in teaching me to understand a story from every perspective but my own. In other instances, I recall the transformative moments I witnessed in the classroom when my students found for themselves the language to explain some frustration they were experiencing in their homes, neighborhoods, or schools. Most recently, I have been tracing the parallels and juxtapositions between Pecola Breedlove and Oluwatoyin Salau to rage about what happens when we don’t confront the ways the systems of white supremacy and heteronormative patriarchy show up in our community, in our bodies, and in our spirits.

Charlotte storytellers engaging with the interactive workbook elements in The Forged Woman at the first SISTORIES community writing workshop. Hosted at The Roll Up Artist Residency in Charlotte, NC. February 2020.

With each remixed reiteration of the “why,” each thinking and rethinking about the birth of this project, I have come to accept that there is no one way to start. Much like the project of rebellion, much like the project of freedom, and much like the debut of our interactive literary magazine, there is no beginning to this time-transcending plot. And as Alice Walker is quoted in the text that grounds the theme of our first edition, The Forged Woman, each of us makes up a part of “the whole story.”

In that text, the writer also outlines a personal historical and psychological construct that Walker has created for understanding Black womanhood. Walker’s framework informs the organization of the fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, visual art, and photography in The Forged Woman and the curation of the writing prompts and reading lists that accompany the pieces. She uses the categories, “The Suspended Woman,” “The Assimilated Woman,” and the “Emergent Woman,” “to describe a series of movements from a woman totally victimized by society and by men to a growing, developing woman whose consciousness allows her to have some control over her life.”

Although Walker defines each category by what she views as the dominating challenges faced by the women in three distinct eras, it is certainly true that there have always been examples of those whose physical and psychological experiences more closely align with another time period. In this issue, we wanted to demonstrate the nonlinear nature of our personal and collective liberation project by inserting the works of southern Black women and femmes into Walker’s conversation and then taking it one step further. It is a portal to past, present and future possibilities.

Her classifications begin with women in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries who were “suspended” within the confines of a brutally violent society that made no room for Black women’s creative existence. The second category, “Assimilated women,” is represented by those in the forties and fifties who experienced less physical violence (in theory) but still suffered the immense psychological toll of coming into form before the political environment had shifted enough to make space for them to live without having to conform to an oppressive standard of being. The final category that she offers is indicative of a new wave of women, of which Walker herself would belong to, who were inspired and awakened to new possibilities of living following the Civil Rights Movement. These “Emergent women” exist at the precipice of an awakening that enables them to offer up “varied, live models of how it is possible to live” (Washington, 214). Before they free themselves though, they must go through a harsh initiation of confronting the world with full knowledge of their psychological and political oppression.

The last section of our debut issue, The Forged Woman, picks up where Walker left off by posing a fourth category. The Forged are those who have made it through the fire of awakening and are a living embodiment of what it could mean to be born free. The Forged Woman is an experiment in possibility, and a call to action that asks for examples of what comes after the emergence. After the uprisings. After we have won the rebellion. Who and what is forged from the fire this time?

Experimenting with the possibilities of what comes next in tandem with explorations of what came before is critically important for building out a radically new world-- especially in this current moment when we are struggling through in the latest chapter of the ongoing fight for Black liberation. Each Black woman who contributed to the magazine, and each Black woman reader who writes themselves into the tapestry of Black femmehood by responding to one of the reflection questions or writing prompts gets us one step closer to the next iteration of freedom. Through this process of connection and reflection we become closer to the whole story that helps me to articulate more clearly the “why” behind SISTORIES.

To read our debut issue, see below. To submit your work for future issues or make a contribution, visit our website at SISTORIES.org.

Ashley Nickens is an educator and story-sharer born in Maryland, raised in Virginia, and made a woman in North Carolina. Her work is inspired by her ancestral connection to Southeastern land, and centers Black femme spirituality and sexuality. She works with the #SmartBrownGirl Book Club, and is the founder of SISTORIES LITMAG, an interactive Black feminist literary magazine and community writing workshop. Ashley is a North Carolina Teaching Fellow Alum and a 2020 Resident Artist at The Roll Up Charlotte. She earned her bachelors in English Education from The University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and is currently working towards a masters in their Liberal Studies program.

IG: @sistoriesclt

Works Cited

Russell, Michele. “Black-Eyed Blues Connections: Teaching Black Women.” All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave Black Women's Studies, by Gloria T. Hull et al., The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, New York City, NY, 2015, pp. 196–207.

Washington, Mary Helen. “Teaching Black-Eyed Susans: An Approach to the Study of Black Women Writers.” All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave Black Women's Studies, by Gloria T. Hull et al., The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, New York City, 2015, pp. 208–217.